“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Benjamin Franklin

In the business world, there’s something called the 1-10-100 rule.

It’s a cost quality measure that seeks to represent the cost of prevention versus the costs of correcting problems or dealing with failure.

Simply put, one dollar in prevention costs can save ten dollars of correction costs and one hundred dollars in failure costs.

Organizations that spend money on prevention or early intervention will save time and resources correcting problems later down the line. This means that if a problem occurs within an organization, there are fewer costs associated with fixing the issue because they have already spent money preventing them from happening.

It’s easy to see how this rule can apply to people wanting to live their best life. For example, in critical areas such as health, finances, and relationships, it’s more beneficial to prevent potential problems before they occur rather than fix them afterward.

Sounds like a no-brainer, right? So what’s the problem?

The Urgency Bias

The problem is that we human beings regularly fall prey to something called the urgency bias. This happens when we prioritize the urgent over the important. Furthermore, we conflate the two, mistakenly thinking that if something feels urgent, it must be important.

Perhaps this bias is wired into our primitive brains, more suited for a time when urgency and importance were more closely linked (e.g. running out of food or being hunted by predators). But in modern times, many things may feel urgent but are not necessarily important, such as phone calls, emails, or text messages.

And the urgent things that are important put us in constant crisis mode, putting out one fire after another.

Trouble is, when things are going reasonably well, there is little incentive to invest time, money, or effort in prevention. In the short-term, it seems unnecessary. Until something urgent happens. A missed quarter. A relationship breakdown. A health crisis.

When a problem or crisis directly confronts us, we’re more incentivized to act. However, we’re also more likely to incur higher physical, financial, and emotional costs.

The Time Management Matrix

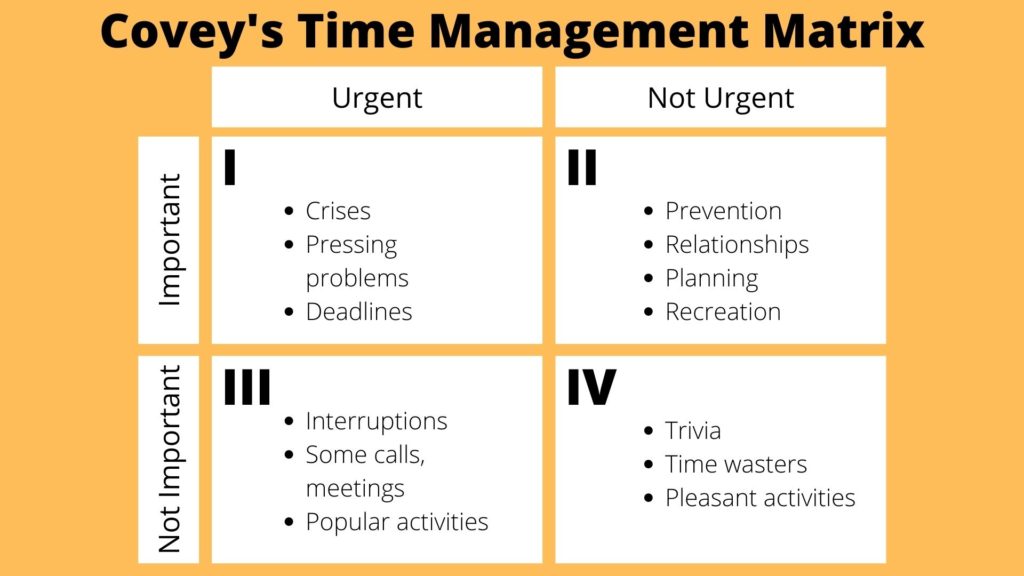

The real challenge is that prevention measures are, by definition, not urgent but are often important. In his book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey presents a time management matrix that illustrates the relationships between activities that are urgent or not urgent versus those that are important or not important.

Here’s a recreated version of his matrix:

Covey identifies quadrant II as the most optimal place for “effective personal management.” He continues:

“It deals with things that are not urgent but are important. It deals with things like building relationships, writing a personal mission statement, long-range planning, exercising, preventive maintenance, preparation—all those things we know we need to do, but somehow seldom get around to doing, because they aren’t urgent.”

Stephen Covey

When we combine this matrix with the 1:10:100 rule, we see that thanks to the urgency bias, we’re often paying the higher costs associated with quadrants I, II, and III, and missing out on the cost savings of quadrant II, the place where preventive action lives.

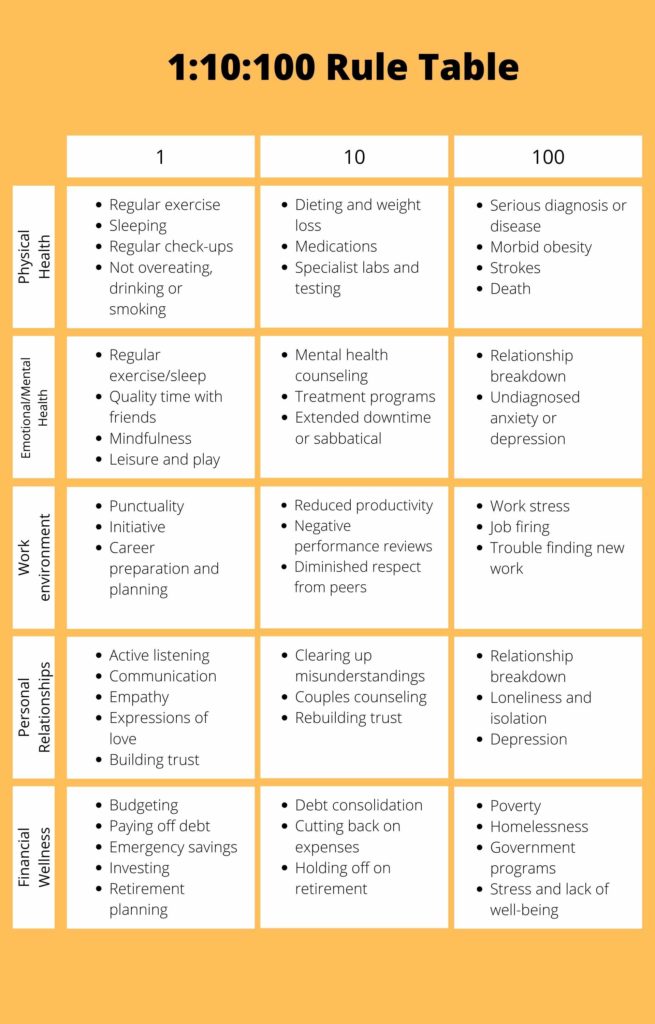

The 1:10:100 rule

How do we combat the urgency bias? By taking a page from the U.S. military and developing your own DEFCON system.

The defense readiness condition or DEFCON is a system used by the U.S. military to indicate its current preparedness for war. The United States Department of Defense uses this scale, which ranges from 5 to 1 to determine how much force should be deployed against an enemy and whether it can defend itself if attacked. DEFCON 5 represents a normal state of readiness while DEFCON 1 represents an imminent threat of nuclear war.

Using a similar system in our personal lives would force us to contemplate what’s at stake when we don’t take preventive measures. It can also incentivize us to act before it’s too late. This is where utilizing the 1:10:100 rule to create a set of personal rules can help. Let’s flesh out a few examples with 1 representing prevention costs, 10 representing corrective costs, and 100 failure costs:

The best investment you can make

Start experimenting with the 1:10:100 rule in areas of your life that you wish to improve. Create your own chart, clearly laying out the best and worst-case scenarios.

Review it every day. Let it motivate you to invest more time and resources in prevention. You’ll find yourself experiencing better returns than you ever imagined.

Thank You 🙂

You’re most welcome!